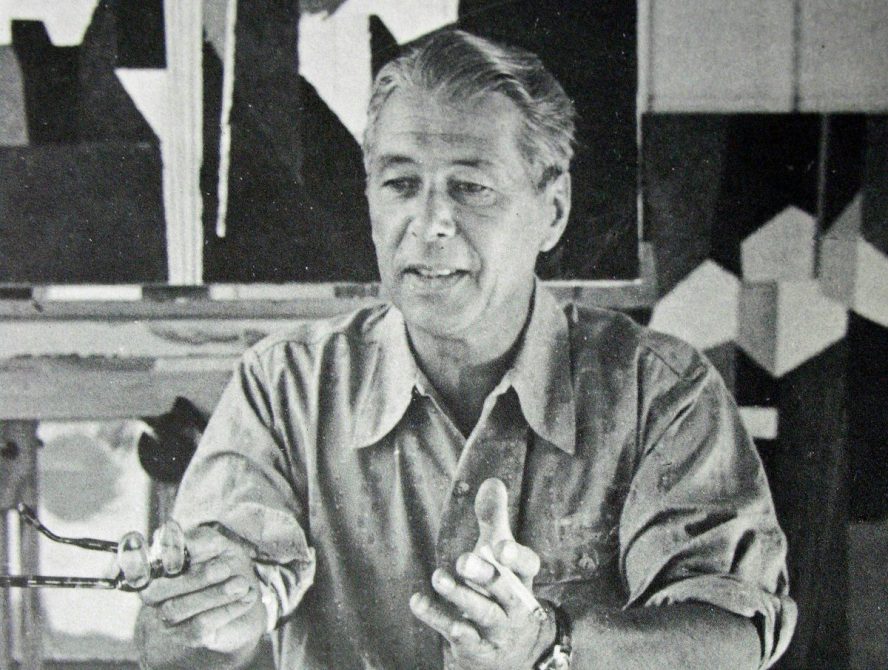

Herbert Bayer (1900-1985)

Education:

Bauhaus, Weimar ‘21 Dessau ’25-‘28Places:

120 E Main 240 Lake 311 North 700 Gillespie Aspen Meadows Reception Center Anderson Park, Aspen Meadows Health Center Kaleidoscreen Koch Seminar Building and Sgraffito Mural Marble Sculpture Garden Paepcke Auditorium Trustee TownhomesStyle:

Bauhaus / InternationalIn 1946, Austrian native Bayer was forty-six years old and an internationally famous designer who had been avidly recruited by Walter Paepcke and his wife Elizabeth to help implement their vision of Aspen as a special community organized around art and culture, a Kulturstaat. An innovator in typography and graphic design, photography and exhibition design in Weimar and Berlin, Bayer designed the universal type font (1925), which was credited with “liberating typography and design in advertising and creating the very look of advertising we take for granted today.”1 He moved to New York City in 1938, where he was a sought-after art director and designer. By 1946, all of his work was for Paepcke, head of the Container Corporation of America (CCA) and Robert O. Anderson, president of the Atlantic Richfield Corporation. A lover of nature and skiing, Bayer had considered returning to his native Austria after the war to open a “little ski hotel.” Instead, Paepcke enticed him with the challenge of remaking the “ghost town” of Aspen, arranged for his purchase of a Victorian cottage in the West End, guaranteed annual consulting fees from both the CCA and Aspen Skiing Corporation, and provided a steady stream of design work on his numerous Aspen properties. A 1955 Rocky Mountain News article stated, “Even in competition with millionaire tycoons, best-selling novelists, and top-ranking musicians, Herbert Bayer is Aspen’s most famous resident.”2

Bayer’s architectural work spans approximately two decades, from 1946-1965. His clients were primarily the Aspen Skiing Corporation, the Aspen Company (Paepcke’s real estate firm), and the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, where he, with Fritz Benedict as the associated architect through the 1950s, designed the Seminar Hall and its sgraffito mural (1953, the first building on the campus), Aspen Meadows Guest Chalets (1954, since demolished and reconstructed), Central Building which housed the Copper Kettle restaurant (1954), the Health Center (1955), Grass Mound (1955, which predates the “earthwork” movement by ten years and was one of the first environmental sculptures in the country), Marble Sculpture Garden (1955), Walter Paepcke Memorial Building (1962), Institute for Theoretical Physics Building (1962), Concert Tent (1964, removed in 2000), and Anderson Park (1970).

Bayer also spearheaded Paepcke’s restoration of Victorian buildings in town, including the Wheeler Opera House and Hotel Jerome, and selected the paint colors for certain Victorians that Paepcke’s Aspen Company decided should be restored in the 1940s. A strong blue, known locally as “Bayer Blue”, has persevered for some fifty years, but is disappearing. His choice of a bright pink for the Paepcke’s West End residence, Pioneer Park (442 W. Bleeker Street) and a bold paint scheme for the Hotel Jerome are local legends. In his twenty-eight years in Aspen, Bayer lived at 234 W. Francis Street, a Victorian house in the West End, and an apartment in a downtown commercial building (535 E. Cooper Avenue). He then moved to Red Mountain where he built his studio and home (1950 [Gordon Chadwick, architect] and 1959, demolished). He designed other modernist residences (1957, 240 Lake Avenue; 1963, 311 North Street) in the West End, located adjacent to the Aspen Institute campus. After his productive career in Aspen, Bayer moved to Santa Barbara, California, where he died in 1985.

Influenced by Bauhaus and International Style principles, Bayer’s architectural designs have simple rectilinear shapes, generally flat roofs, expanses of glass, cantilevered balconies, basic geometric shapes, industrial materials such as steel frames and cinder blocks, and use primary colors, whites, and grays. Bayer believed in the Bauhaus concept of designing the total human environment, that art should be incorporated into all areas of life, and he designed logos and posters as well as landscapes and buildings that brought high modernism to Aspen.

1 Joanne Ditmer, “Schlosser Gallery Host to Major Bayer Show/Sale,” Denver Post, October 1, 1997.

2 Robert L. Perkin, “Herbert Bayer Changing the Town’s Face,” Rocky Mountain News, September 27, 1955.