Fritz Benedict (1914-1995)

Education:

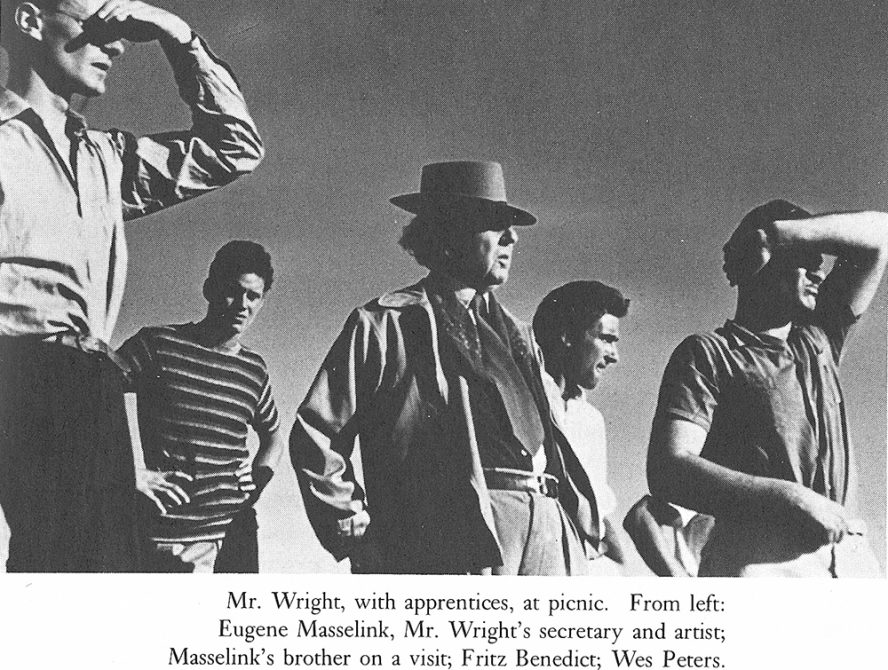

Wisconsin ‘38, Taliesin ‘38-‘41Benedict, thirty years old when he mustered out of the 10th Mountain Division, was the first trained designer to arrive in Aspen after the war. Born in Medford, Wisconsin, he had earned a Bachelor’s Degree and a Master’s Degree in Landscape Architecture at the University of Wisconsin in Madison before joining Wright’s Taliesin in Spring Green in 1938 as head gardener. He appreciated Wright’s philosophy of integrating architecture and landscape, and, along with the other apprentices, he migrated between the two Taliesins for the next three years. On one of those Arizona-to-Wisconsin drives, in 1941, he first saw Aspen. An avid skier, he stopped for the National Skiing Championships and decided that the mountain town would be a good place to settle. That first impression was later confirmed when he was stationed with the US Army’s 10th Mountain Division, an élite group of skiers, at nearby Camp Hale, north of Leadville, and visited Aspen on the weekends.

In 1945, Benedict purchased a 600-acre ranch on Red Mountain for $12,000, which he scraped together from his army pay, a loan from his mother, and selling his car. A self-described “hippie,” Benedict planned to live in a small cabin and operate a subsistence ranch, then a dude ranch, saying that the mystique of ranching appealed to him as much as skiing. Eventually he added odd-carpentry and designed one house a year, rustic houses that evoked the organic architecture of his mentor.

Benedict’s architecture extends from the 1940s into the 1980s. His earliest projects were residences, such as a cabin at 835 W. Main (1947); a private dwelling for novelist John Marquand (1950, demolished) on Lake Avenue in the West End overlooking Hallam Lake; modern chalets at 625 and 615 Gillespie (1957, demolished); and the Edmundson House (1960, demolished), also known as the Waterfall House, after Wright’s famous Fallingwater. In 1967, Benedict created Ski magazine’s first “ski home of the month,” in what was intended to be a regular feature on affordable well-designed vacation homes. One of his modest “Hillside Home” designs, built at 1102 Waters Avenue by Bill Geary, still remains in the Geary family.

As Aspen’s economy revived, Benedict also designed numerous commercial and public buildings. In addition to early Aspen Institute buildings through the 1950s, he and Bayer collaborated on the Sundeck warming hut (1946, demolished). Benedict also designed the Bank of Aspen (1956, 119 S. Mill Street), Bidwell Building (1965, E. Cooper), the original Pitkin County Library (1966, 120 E. Main Street), Benedict Building (1976, 1280 Ute Ave), and the Pitkin County Bank (1978, 534 E. Hyman Avenue). He designed the base lodge at Aspen Highlands (1958, demolished) and planned the entire ski area at nearby Snowmass (1967) as well consulting at Vail (1962) and Breckenridge (1971). In the 1960s, he greatly influenced Aspen’s condominium development and residential shift from downtown to the east, designing the Aspen Alps (1963); Aspen’s first large-scale urban condo, Aspen Square on Durant and Cooper Avenues (1967); Aspen’s largest condo complex, the Gant (1972); and the Crystal Lake condos (1976), at Aspen Club. In total, Benedict designed and renovated more than 200 buildings in Aspen and Snowmass.1

The prolific architect was known for setting buildings into the landscape in a harmonious way, which reflects his landscape training and Wright’s influence. At Taliesin East, he had been in charge of the gardens, while, at the Arizona camp, he worked with the natural desert landscape, even moving cactuses. He pioneered in passive solar and earth shelter design, exemplified in the Marquand house (1950) and his own solar and sod-roofed residence at Stillwater Ranch (1958). His masterwork, the Edmundson Waterfall House, an homage to Wright’s Fallingwater, shared many of the characteristics of Wrightian design—dramatic cantilevered structure, massive chimney as the anchor, strong horizontal emphasis, low-pitched roof with deep overhangs, mitred windows in the corners, and, above all, an intimate and specific relation to its site.

Benedict’s office played a critical role in Aspen’s emerging architectural scene, launching Ellie Brickham, Jack Walls, Robin Molny, Ellen Harland, Theodore Mularz, George Heneghan, Dan Gale, John Rosolack, Robert Sterling, Janver Derrington, Dick Fallin, Dierter Zenker, Tom Duesterberg, Bruce Sutherland, Arthur Yuenger, and Harry Teague, among others. Molny set up his own office in the late 1950s and later hired Yuenger. Mularz opened his practice in 1963 (employing Aspen’s third woman architect, Jean Wolaver-Green), leaving on such good terms that his wedding reception (to Bayer’s secretary, Ruth) was in the Benedict greenhouse. Walls and Sterling became partners in 1968. Heneghan and Gale were partners from 1966-1969. In the 1960s, when Benedict took on large-scale ski resort planning and design, his firm increased to thirty-five.2

Benedict also embraced the traditions of the Taliesin Fellowship; both his home and workplace welcomed young architects. In 1946-1947, Taliesin fellows George Gordon Lee and Gordon Chadwick lived and worked with him on his Red Mountain ranch, and Chadwick, a licensed architect, designed several Aspen residences and Bayer’s Red Mountain studio (1950) with him in the late 1940s. Curtis Besinger returned to sojourn with the Benedicts regularly each summer, starting in 1956. After his years at Taliesin (1949- c. 1954), Robin Molny started his Aspen career in Benedict’s office, then set up his own practice. Benedict encouraged Boomerang Lodge- owner Charles Paterson to spend three summers in Spring Green (1958-1960).

Aside from his architectural contributions, Benedict influenced the Aspen environment in other ways. He served as the first chairman of Aspen’s Planning and Zoning Commission, developing height and density controls, open space and preservation policies, a City parks system, a sign code, and ban on billboards. He played a significant role in the founding of the Aspen Institute and the International Design Conference and served on the board of the Music Associates of Aspen for 35 years. He was the father of the 10th Mountain Hut System, established in 1980, and he and his wife donated more than 250 acres of land within Pitkin County for open space.

1 Mary Eshbaugh Hayes, Dedication plaque on “The Benedict Suite,” Little Nell Hotel, Aspen, Colorado.

2 Brian Clark, “Ski Country Style,” Ski Area Management 25 (March 1986): 55-57, 78-81.